The Uncontacted in the Peruvian Amazon Rainforest

- LatAm Dialogue

- Jun 27, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: Aug 11, 2020

By Maria Gracia Valdivia-

Have you ever wondered what it would feel like to live isolated from society? Completely marginalized from all that is westernised and technological? This is exactly how the uncontacted indigenous groups from Peru’s Amazon Rainforest live. These uncontacted indigenous groups are communities who live in complete isolation from the rest of the world. They do not interact or communicate with the outside world and live their lives detached from what many would consider to be ‘civilisation’ and ‘modernity’.

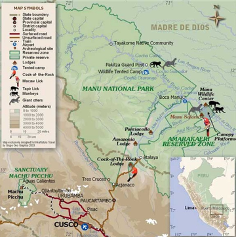

There are around 15 such indigenous communities in the Peruvian rainforest. Some of these communities, such as the Mascho Piro, live close to the Manu National Park. Others tend to live closer to small villages and more populated areas.

Almost all of these uncontacted peoples are considered nomads as they move around the jungle depending on the season and their immediate needs. However, the movements of these communities tend to be within a general area that they are already familiar with. This is because moving to other areas poses a threat to their livelihoods as they are less familiar with the land.

Despite this, recently, many members of the Mascho Piro community, who originally lived beside the river Pinquén within the Manu Natural Park, have also been sighted near the border of the river Alto Madre de Dios, where they are more exposed to other people. Carlos Soria, the ex-secretary general of the National Service of Protected Natural Areas of the State (SERNAP) in Peru, has stated that he finds it curious that indigenous groups are moving to areas where they are becoming increasingly more exposed to the modern world.

Considering the world we live in and how technology and environmental factors shape a great part of our lives, it is anticipated that these uncontacted communities will become increasingly threatened. Although these communities live, or try to live, as far away from civilization as possible, they are still at risk of some undeniable threats of both a human and physical nature.

According to Soria, the Mascho Piro are now living in areas that are witnessing an increasing amount of human transit which is threatening their community. Due to the community’s lack of antibodies and the fact that most of its members have never been exposed to certain modern diseases, if they come in contact with people from outside their community, many indigenous peoples could easily become infected and this could have fatal consequences. After the first contact with another human being, it is anticipated that over half of the community could die. In extreme cases, the entire community could be wiped out.

Another direct threat faced by uncontacted communities in the Peruvian Rainforest is caused by oil companies. The Peruvian government actively encourages new companies to expand their projects throughout the Amazon region. The government has deliberately signed contracts with oil companies involving up to more than 70% of the whole Amazon region, including the areas where these isolated communities live. In the past, for example, the oil and gas company Shell was to blame for more than 50% of all the Nahua community’s death. Remembering the incident, a woman from the Nahua community said “My whole village died. Their eyes started hurting, they began to cough, they became ill and died right there in the jungle”.

Furthermore, the lands of these uncontacted peoples are being increasingly seized by the government and their communities destroyed. The ILO International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 169, is the only international law designed to protect indigenous and tribal people’s rights. The ILO Convention 169 gives these people the right to own the land they live on and use, to make decisions about projects that affect them, as well as equality and freedom. Consequently, every country that ratifies the convention gives indigenous/tribal communities a greater chance to survive and live without fear of persecution. Having said that, only 23 countries globally have signed it, despite its existence since 1989. Therefore, although the ILO Convention 169 protects indigenous/tribal peoples’ rights to their own land, most governments won’t enforce it, and consequently, noncontacted communities will most likely remain in a vulnerable position.

This leaves us open to wonder various questions: to what extent are noncontacted communities completely isolated from the ‘real’ world, and modern technology? Have they ever seen planes flying overhead? Or had encounters with tourists and other people that have happened to cross their paths. If so, what do they make of it all?

Bibliography:

https://rpp.pe/peru/actualidad/captan-a-indigenas-no-contactados-en-selva-sur-de-peru-noticia-446318

Comments